The objects classified under African art were not primarily created to be looked at. They were made in order to be used, whether in this world or in connection with the other World. While Western art lovers are fascinated by the forms of African artefacts, these objects all had a pragmatic purpose in the society in which they were made.

No matter whether a loom or an ancestor figure, a mask or a stool, all of them were used in some ritual, political, social or everyday context. Art as an end in itself, art for arts sake, was practically unknown in traditional Africa. If the objects did not fulfil their purpose adequately they were useless. This applied to a leaking water jar just the same as to a power figure that failed to protect its owner from harm.

To apply the label ‘art’ to African objects is therefore to place them in a Western category that had no equivalent in African societies. The concept of art as something with no practical use, as "l'art pour l'art", in contrast to the utilitarian objects made by craftsmen, simply did not exist. As in the medieval times of European history, there was in Africa no separation between art and craft. It is significant that most African languages do not distinguish these two categories whereas the Western world largely continues to do so today.

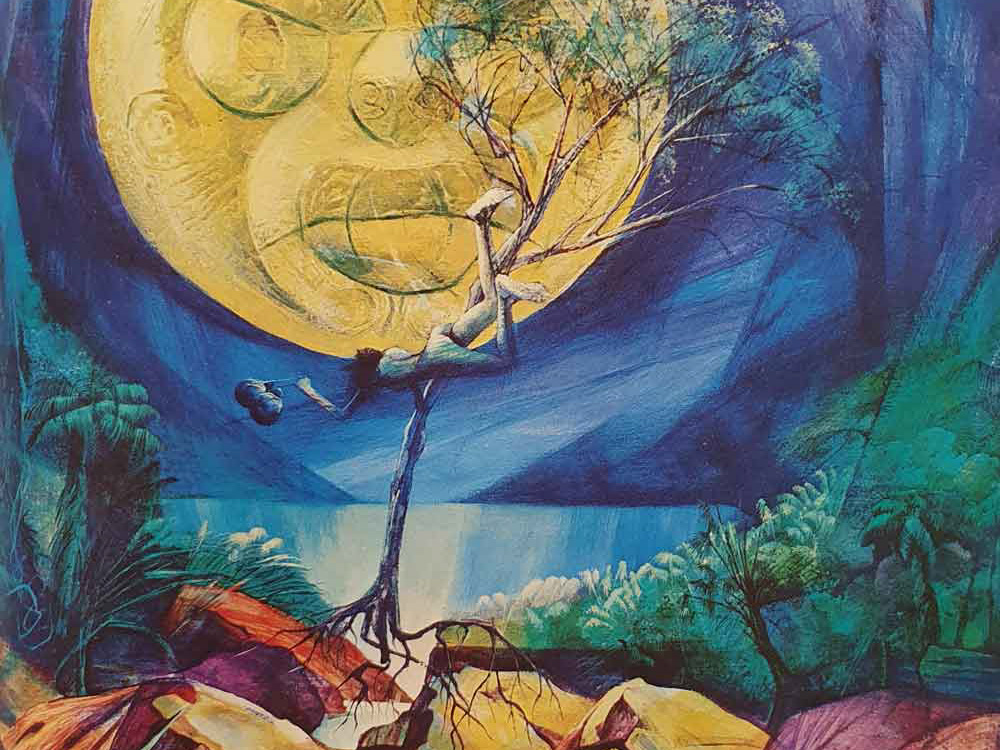

The spoken word and images, not writing, were the chief means of expression for societies in Africa south of the Sahara during the greater part of their history. Sculptures therefore assumed an important role in social organisation and interpersonal relations and conflict. Certain objects were a means of communication not only between the living but also between the not yet living and the no longer living members of a society. The artworks were capable of mediating between the earthly and Supernatural. They were points of contact between the human and superhuman World.

In the world views of many African societies, the universe consists of visible material and invisible spiritual elements. The world of the living and the supernatural world of the not yet living and the no longer living exist side-by-side, overlapping and penetrating each other. They are not independent and separate from each other, but unusually conditional. The borders between this world and the other world are pervious and can be crossed on certain occasions, mostly by ritual specialists. People with this vocation are able to make use of the forces from the other world for certain purposes in this world.

In large parts of Africa the ancestors are not conceived as actually dead or living in a far distant world but rather as being present among the living and able to influence the lives of their descendants. The ancestors watch over the fertility of animals, fields and humans and bring peace, harmony and prosperity in the community. They act in general as intermediaries between humans and supernatural forces and beings. However if moral or other social rules are breached, or if the ancestors are neglected, they react with punitive sanctions. Because the ancestors are closely linked to the living and important aspects of their life, it is vital to treat them with respect and to obtain their goodwill through prayers and gifts. Sculptures are one of the best means of establishing contact with the inhabitants and forces of the other world. Through them, supernatural beings can participate in the world of humans, and humans can have an effective influence on other worlds beyond this one, by invoking forces there to act in the interests of individuals and the community, and ensuring that harmful influences are warded off, neutralised or transformed into positive energies.

The majority of African figures have proportions that are different from those our eyes, trained in western visual traditions, are accustomed to. This is in large part due to the symbolism and hierarchization of body parts. The head of the belly with the navel are often oversized, because they are considered to be the link to the world of the ancestors and therefore more important than the arms and legs, for instance, which may be abnormally short. Many African figures have projecting primary sexual organs of female breasts, a feature which Western collectors in the first half of the 20th century found either particularly attractive or particularly obscene. However, the emphasising of these body parts is not a sign of voluptuousness but was intended as a symbol of fertility or male potency, the continued existence and prosperity of the community, and the social influence that is derived from having many descendants.

The figures are not normally likenesses of real people, past or present, but are timeless, ideal images representing the sacredness of the social and cosmic orders in the form of high-ranking ancestors. A realistic image or portrait of the person would go against these intentions, since such "naturalism" is conceived of as accidental and bound by time and situation.

Nevertheless, ancestor figures were often identifiable through such features as hairstyle, scarification or badges of rank. In addition it must be remembered that there were regional traditions of perception which allowed the members of a particular community to identify by name representations of persons which to an outsider may appear to be completely idealised.

When presented in western exhibitions and collections, African objects are usually torn completely out of their contexts and brought in line with established conceptions of "art".

African masks in European collections, for instance, are usually reduced to the wooden face, while at “home” they are embedded in performances with music and dance, actions and audience reactions, and interactions with other masks; they have a set of accessories in the form of a costume made of vegetable fibres, cloth, feathers or animal skins, and sometimes other items such as stilts, musical instruments, whips or switches.

In their original context, some masks were dangerous or ritually significant, and non-initiates were not allowed to touch or even see them since they were associated with extremely powerful forces that could cause death, incurable diseases or madness. All this is of course lost when the object is placed in a museum.

The most important point about the majority of masquerades is not that the masks hide the dancers but that they reveal beings or powers that are normally hidden and invisible.

Exhibitions of figurative sculptures in western museums concentrate mainly on external, formal aspects. Yet in the original context their most important and most essential elements were often not visible. In the case of mirror figures from Central Africa, the powerful effects are not concentrated in the carved wooden figure itself but in the special substances that have been charged by a ritual expert, programmed for particular purposes, and hidden in hollows behind bundles of cloth or mirrors.

Many people still refer to African art as tribal art that is characterised by different tribal styles. This idea is based on a conception of African art according to which each tribe is thought of as having created its own artistic universe, so that each African tribe has only one single style. This popular "1 tribe, 1 style" model would mean that the Artists within one ethnic group were restricted by very narrow stylistic limits.

It would also mean that African art and African cultures were like islands, having very little contact with each other. However, it was the Colonial powers who for political reasons found it convenient to force the ethnic groups in Africa into the straitjacket of tribes.

Frequently it had little to do with the lived realities of the African people. Indeed many tribes such as the Bamana, Dogon or Fulbe in Mali, were constructed as units by the Colonial authorities for administrative reasons.

But among people with creative occupations, such as smiths, metal casters or sculptors, there were many itinerant craftsmen who worked for clients from different ethnic groups. As a result, stylistic features of the clients society were often mixed with the sculptors personal style and the sculptural conventions of his own ethnic group, in contrast to the '1 tribe, 1 style' model, it is not uncommon to find transitional and mixed styles. In addition, it is not unusual for one style to be found among several tribes, or the single tribe or even a single institution to have several different styles.

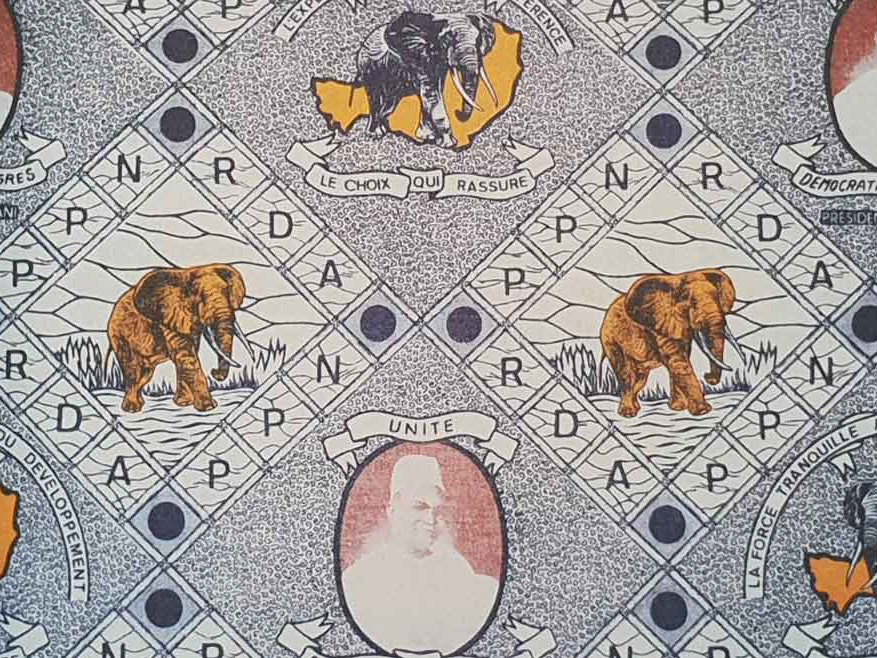

Tribal art also fails to do justice to court art from the kingdoms, feudal Empires, city-states and commercial empires of Africa. This was elite art created exclusively by highly specialised artists on behalf of dignitaries and rulers for purposes of representation and legitimation.

The court artists came from different parts of the kingdom and belonged to various ethnic groups. Research has now shown that the rulers and nobles of different kingdoms were in contact with each other and entered into alliances over enormous geographical distances.

Comparatively natural sculptures could be produced beside very abstract ones. For African societies did not exist completely independently of each other.

Up to this day, works from Africa are presented explicitly or implicitly in museums, exhibitions and publications as works by nameless beings. The descriptions usually give only the country of origin of the tribe to which the work is thought to owe its existence.

This is in serious contrast to the current way of handling Western art, in which interest is focused on the name of the artist and art history concentrates on the work, life and creativeness of persons who are known by name.

Behind this fundamentally different approach to creative and art works from Africa is the idea that traditional African artists represent their community and use their skills in the service of century-old traditions.

In Europe and the US, African artists are conceived of as more or less skilled imitators of collective traditions with strict rules that do not admit any kind of individuality. It was, and often still is, believed that it was impossible to break away from the narrow stylistic canon of communal cultural traditions, for which reason the works should be understood as creations of the artists communities rather than those of creative individuals.

And this despite the fact that in the 1930s Hans Himmelheber had observed in the regions of West Africa visited by him that many sculptors were "very individual" personalities who constantly departed from tradition.

Famous in this respect is the remark by Roslyn Adele Walker, to the effect that traditional African artists were never anonymous and that their names were known to their clients and probably also to the people who saw their works. Walker argued that the names of the artists were not handed down to us for reasons that can be described as racial and cultural: quite simply, no one asked about them.

Recent research on Yoruba sculptors in Nigeria and in the Republic of Benin has shown that certain sculptors had a supra local and even supra regional reputation there at particular times and that they were sent for over great distances to come and carry out commissioned works because of their unmistakable style.

It has also been shown that the semantic dimension of ‘Asa’, the Yoruba word for tradition, covers not only ideas of continuity and survival, but also ideas of change inherent to the nature of the creative process. Tradition for the Yoruba means not only imitating older models, but it also encourages sculptors to exploit and modify the traditional models. Apprentices spent many years serving experienced sculptors and frequently gained experience themselves by travelling about and working in different places. But the ultimate aim of their training was not to copy and imitate the master; rather, the aim was to reinterpret what they saw and learnt, and to redefine all the forms - yet at the same time remaining readable for the public and the owners of the Works.

Among the Igbo in the Southeast of Nigeria, change is a fundamental aspect of society that automatically also applies to art.

However, the lack of artist’s names behind the works cannot be explained only by the ignorance of Western colonialists and collectors. The ideal Yoruba sculptor, to take one example, was permanently on the move, earning his living by accepting commissions in different regions. But with the passage of time, only his works would be well-known, while his name as the maker of the works was forgotten.

Frequently sculptors worked together with colleagues or relatives in a workshop and artefacts were attributed only to the master or eldest member of the group, although the work was actually divided among several people.

Overall, recent research has clearly shown that the cult of the individual in the sense of the importance attached to names and individual office in the modern Western world, was unknown in many African societies.

For a long time studies of African art concentrated on the common features of works from a single region instead of on their differences but this practice has begun to shift. Westerners first had to be opened to the dynamic nature of artistic traditions in Africa and to the creative freedom allowed to individual artists.

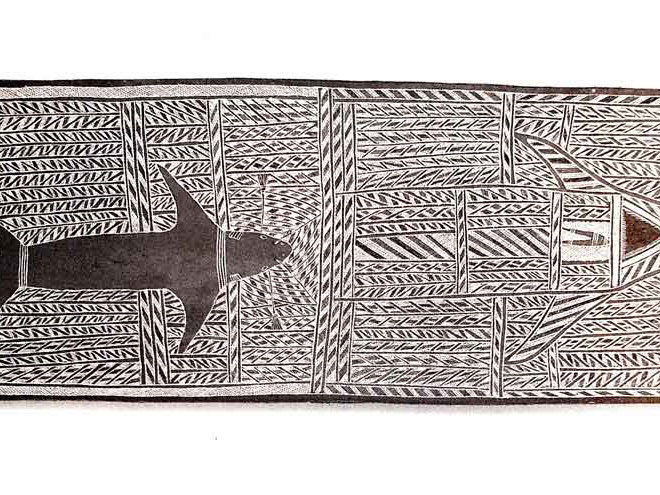

This starts with the choice of the type of wood and the striving to do justice to the materials used, which requires a high level of experience, sensitivity and flexibility. With many wooden sculptures, the type of wood to be used was selected according to criteria such as hardness, weight, weather resistance, shape and size. In addition, the sculptors usually worked without models or preparatory drawings, which meant that they had to have an exact mental idea of the finished objects before beginning work. And since the sculptures were often made from a single piece of wood, it was almost impossible to correct errors.