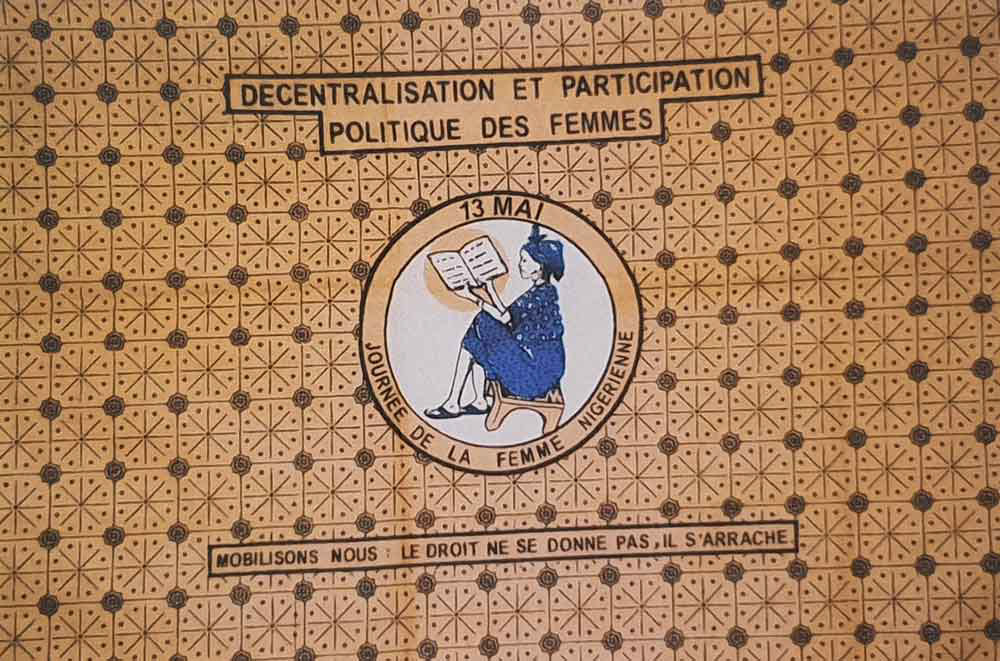

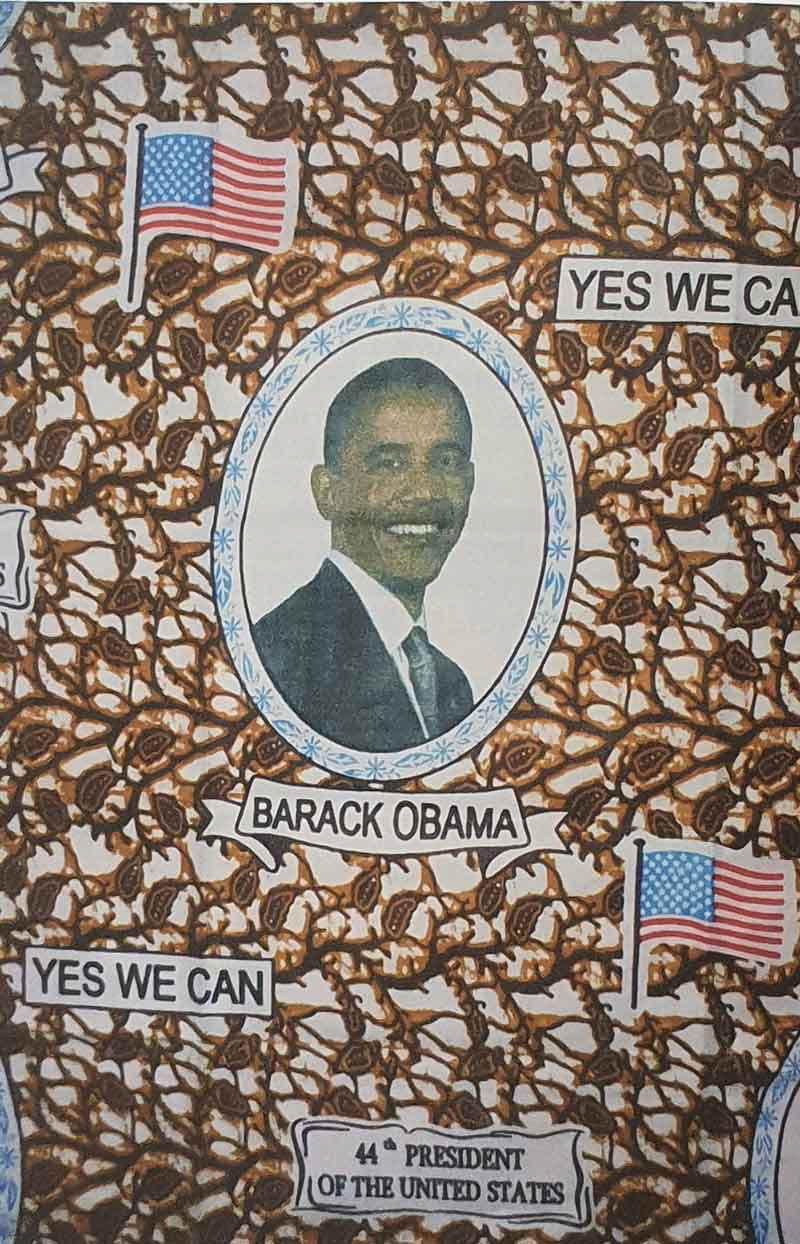

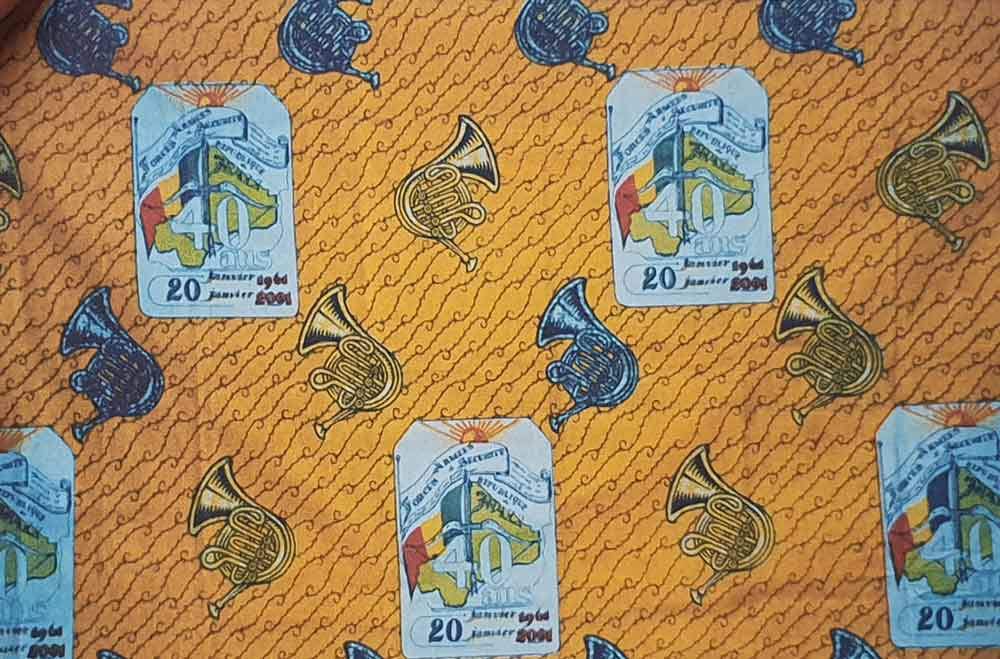

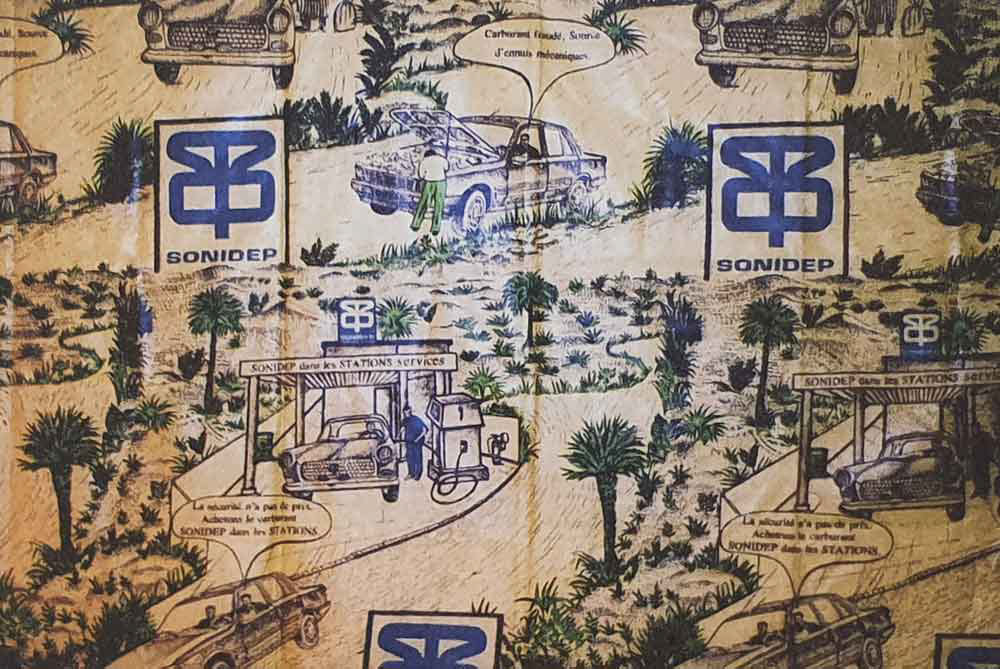

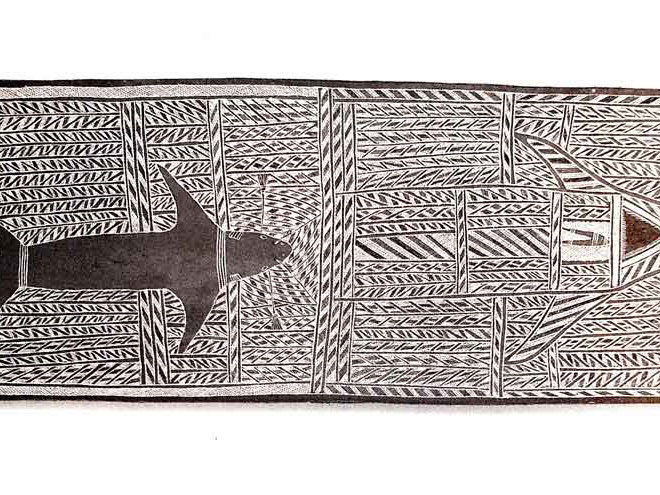

Cotton wax prints in the Sahel region of Africa constitute a means of social, political and religious communication. In fact, throughout the African continent, the brightly coloured, boldly graphic cotton fabric confirm that these textiles are more than mere pieces of Cloth. Wax prints most often serve the function of vibrant art form efficacious method of transmitting cultural messages and ideologies, and pedagogical tools.

Commemorative wax prints are produced for government agencies, businesses, organisations, heads of state, celebrities, religious leaders, airline, sports teams and tournaments, utility companies, national holidays, funerals, wedding, national unity slogans, and various other functions.

Wax prints thus become a way to wear contemporary African cultural history to promote cultural ethnic pride and to continue the tradition of bright coloured, distinctive attire in West Africa.

For starters, one of the various aforementioned entities initiates a request to a textile Mill for the creation of the crop. The clients participating in the design, logo, Insignia, motifs, and colours that will be selected for manufacturing. Once the design has been approved, and number of bolts to be produced is determined based on sales to projected clientele and, of course, financial backing.

Completion of the finished product, merchants are able to buy large quantities of the printed fabric in advance to organise distribution. Since the lightweight wax print is subsidised and produced for popular consumption, it is priced to be affordable for the masses.

On the day of the commemoration, all persons in attendance will appear dressed in the cloth. Most often, the style of the garment is not specified, allowing for creativity and unique expression. The uniformity is in the cloth itself. Unity is established as participants recognise one another during the event and long after, even years later. The cloths are special because a limited quantity of each commemorative cloth will be made available. Only and where instances does the textile factory every release the same pagne or reproduce and identical arrangement of motifs and colours.

The production and wearing of commemorative cloth became an integral, even inextricable aspect of contemporary black African culture. It is a social institution whereby the cotton wax print has been established as a constant feature of African identity that is distinguishable from the use of such class in other world cultures. In Africa, the industrial wax print commemorative cloth is a daily ritual of celebration.

African wax prints are popular, colourful, batik style cotton fabrics manufactured throughout central and western Africa by national textile companies.

The wax fabric, also known as Ankara or Dutch wax prints, can be sorted into categories of quality according to the processes of manufacturing. The producer, name of the product, and registration number of the design are printed on the selvedge, protecting the design and advertising the quality of the fabric. The wax fabrics constitute capital goods for African women. Therefore, they are collected commensurate with one's financial means.

The process of making cloth was originally influenced by an Indonesian (Javanese) method of dyeing cloth by using wax resistant techniques. Wax is melted and then patterned across the blank cloth. Thereafter, the cloth is soaked in die, which is prevented from covering the entire cloth by the wax. If additional colours are required, the wax and soak process is repeated with new patterns.

Ankara is different from batik in that it is made through the Dutch wax method. The method was created by the Dutch during their colonisation of Indonesia in the 1800s, with the goal of flooding markets with cheap machine-made imitations of batik. Unfortunately for the Dutch, these imitation wax resistant fabrics did not successfully penetrate the batik market. They did however experience a strong reception in West Africa when Dutch trading vessels began introducing the Fabrics in those ports.

The Dutch wax prints quickly integrated themselves into African apparel. Women used to fabrics as a method of communication and expression, with certain patterns being used as a shared language, with widely understood meanings. Many patterns began receiving catchy names. Overtime, the prints became more African inspired, and African owned by the mid-1900s. They also began to be used as formal wear by leaders, diplomat's, and wealthy members of society.

In recent years, due to the drop in cotton prices along with National crisis, the once booming textile industry in the Sahel has turned to full or semi privatisation for survival. According to one expert, Senegal's main export is cotton, yet there is a significant amount of importation of textiles, mainly from Asian countries. In 1996, Niger was pressured by the international monetary fund to sell Soitextil. The company was suffering from High production costs and The Rise and competition of cheap imports from Asian countries. 2 years later, Sonitextil was bought by China Worldbest Holding Limited. The formerly state-owned factory became the property of the Chinese government.

Much like its counterparts, Comatex, [in Mali] has had to evolve in order to survive. The Enterprise, now known as comatex S.A., is a joint venture between Covec (China Overseas Engineering Group Co Ltd) as holding company and the Mali government as shareholder. [It has] become the largest textile producer in West Africa, with more than 1400 employees.