The ancient city of Kano in northern Nigeria was for centuries one of the main terminals of the caravan trails from the Maghreb across the Sahara and down to West Africa. A bustling marketplace, it attracted people from all over Africa. As in neighbouring Sokoto, goat hides were tanned there to produce 'Moroccan' leather, and there were also blacksmithing and jewellery quarters. But the most important industry was indigo dyeing. Indeed, in pre-industrial times Kano is reputed to have provided most of the indigo dyed cloth worn throughout the Sahara. As in the rest of Africa, this cloth has now largely been replaced by mill made materials and factories clothing and the natural indigo by synthetic dyes of many hues. Nevertheless, Kano's Kofor Mata dye pits are still in operation today after more than 500 years. Indigo dyeing is widespread in West Africa. The dye pits and vats of Kano and Yoruba land in Nigeria and of st. Louis in Senegal are justly famous.

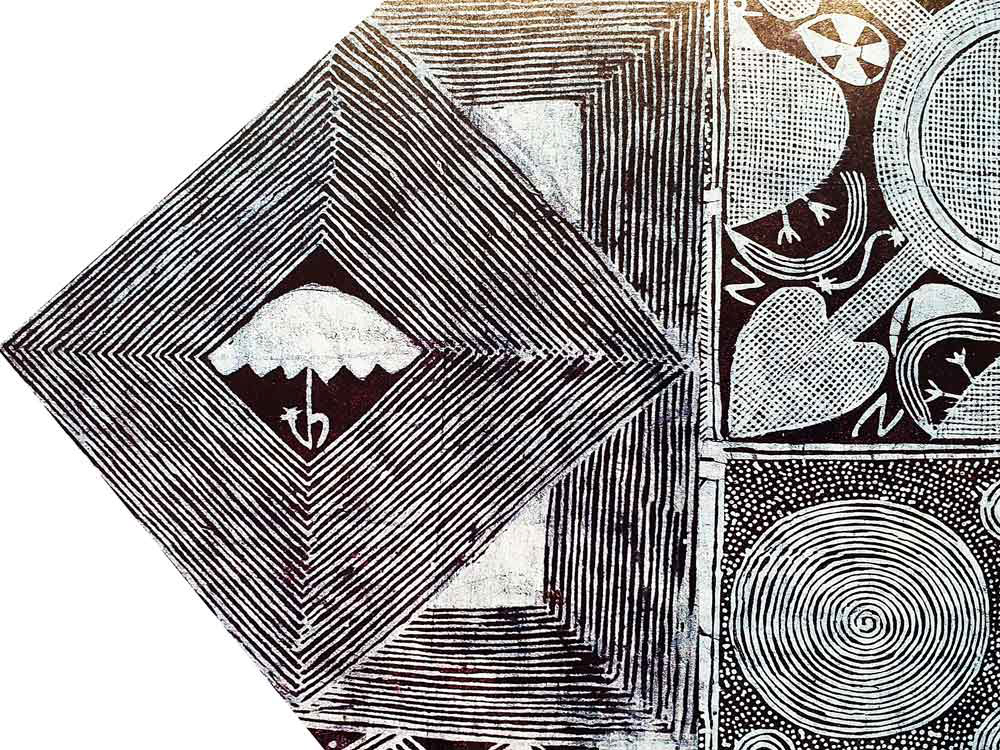

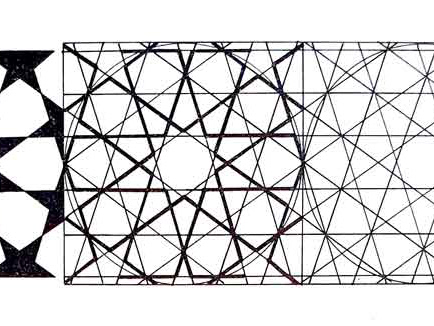

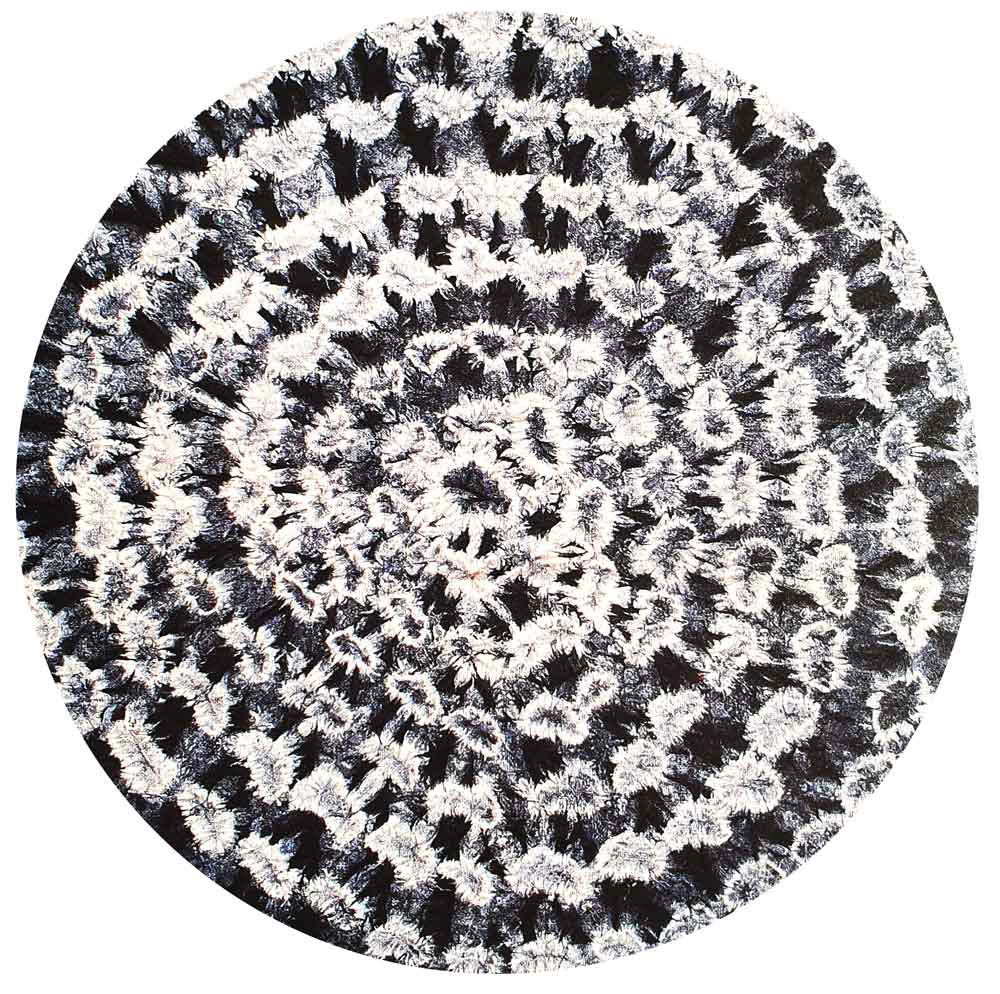

Regardless of the dye used, methods of creating white motifs against an indigo blue background remain the same. Usually a resist is introduced into the cloth before it is dyed by stitching or tying sections of it with raffia or cotton thread, which is pulled extremely tight to prevent the dye from penetrating the enclosed cloth. During the 20th century machine stitched resists became common in Nigeria and the senegambia region. Wax is widely employed as a resist medium for drawing designs onto fabric, and in Nigeria cassava starch is the resist used to produce the charming indigo dyed adire cloths of Yoruba land. Hand decorated adire cloths are traditionally made by women and stencil versions by men.