What was the role and significance of Polynesian objects in their original contexts of use?

Objects were fundamental to relationships, and they did more than symbolise them, they embodied them. This distinction is important because a piece of barkcloth, for example, presented as an offering was not a symbol in the way that the letter 's’ is a symbol of the sound ‘s’. A barkcloth offering can be seen as an embodiment of the women who produced it, and as

such it becomes a form of sacrifice, specifically a sacrificial substitute equivalent to their

bodies, with all the life-giving potency which that implies.

If we are sensitive to indigenous categories we find that certain things were linked, or

were regarded as equivalent: a god image and a chief, for example, or a magnificent

feathered cloak and an apparently humble fish hook. All four were regarded, on specific

occasions, as vehicles suitable for the physical manifestation of divinity in the mundane

world. The cloak and fish hook were also classified as important 'valuables' - objects

suitable for ritual presentation. This significance as valuables is separate from, though

linked to their uses as garments and fishing equipment.

Religion in Polynesian contexts was not an aspect of existence which could be separated

off from politics, economics or social life. Religion encompassed all these domains of

human activity, so that authority, leadership, conflict, the distribution of goods and ser

vices, kinship and affinal relations (with those to whom you are connected by marriage)

were all aspects of an overarching religious context. The success or effectiveness of any

of these areas of human endeavour was ultimately dependent on having an active and

appropriate relationship with god or gods, with divine beings who could affect the

mundane world. In this respect, human action or efficiency alone could not guarantee

success. Divine favour was also necessary.

The relationship between myth and history is a complex one in societies with unwrit

ten languages. Many Polynesian myths were recorded after writing was introduced as a

result of Christian conversion, and they were subject to tidying-up processes by well

meaning people, locals and Europeans, who wanted to present a coherent picture of

Polynesian cosmology.

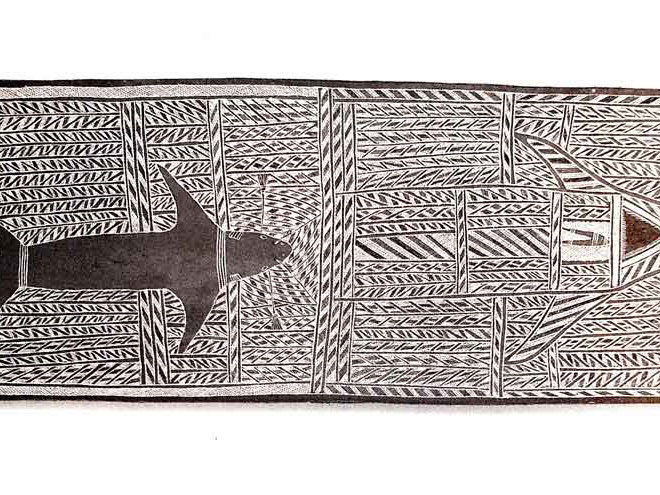

The importance of complementary pairings in Polynesian cosmology and religious

practice is reflected in the ritual significance of sea and land. These are the two major

domains in which Polynesians lived their lives and which provided the major resources

that sustained them.